IN A STRANGE TOWN.

Chapter 4. Sept 9 2021. Text by SC. # Comments

Travelling requires flexibility even at the best of times. Travelling during year two of a global pandemic pushes that to the next level. As we have all learned over the past 18 months, COVID-19 and its variants create fast-changing and unpredictable situations. About two months before our departure date, we changed our starting point from Latin America, where COVID rates were very high, to Central Asia. A month later, we changed our itinerary again due to the quickly evolving situation in Afghanistan, adding Georgia and Turkey to the itinerary. At the time, both regions were open to visitors and had very low COVID rates. By the time we crossed into Georgia in August, it was number one in the world in cases with 116 per 100,000 (compared to Canada, which is currently at 10 per 100,000). Meanwhile, in Peru and other Latin American countries that we’d postponed, the cases have cratered (Peru is currently 3 per 100,000).

So flexibility, a keen eye on what the research is saying about the effectiveness of the Moderna vaccine, and a degree of risk tolerance have all been necessary. That said, it has been fascinating to observe and experience how people and governments are responding to the pandemic in different parts of the world. You quickly realise that you can’t control what people around you do, and this is particularly true when you are a guest in a country and you don’t speak the language. COVID protocols and norms therefore quickly become like other societal practices that are important to observe and adopt when a guest.

Many friends and family have asked a reasonable question, one that we ourselves wondered about before we left: what exactly is it like to travel right now? Are people covered up in masks or not? Are the streets booming or quiet? How do locals view the vaccines, and are they available at all? How much of a pain is it to cross borders? And most importantly, do the people really want you to visit anyway?

MASK WEARING

So far, we have visited six countries and the degree of mask wearing and what it seems to represent has varied tremendously within and across countries. In Dubai, there was a strict mask mandate both inside and outside, which was very much followed as well as being enforced by armed military stationed at checkpoints on the street. Before realizing there was an outdoor mask mandate, a guard barked at us in Arabic to put on our masks when we were walking down an empty street. We figured it out from there. Despite how deeply uncomfortable it is to wear a mask in 45 C desert heat, as well as being largely pointless, people are complying. Authoritarian regimes are good at achieving that outcome.

In some countries, mask wearing also seems to serve as a social signal. In Bishkek, the Kyrgyz capital, mask wearing was mostly limited to those patronizing or working in hip cafes and restaurants. There it appeared to signal class and worldliness. In Texas, it seemed to largely communicate whether you belong to the left or the right. In Austin, as we walked down one of the main streets with hip stores, almost all of them had signs that prompted customers to wear a mask, either through humour or clear direction. That is, except the cowboy boot and Stetson hat store, where, despite being right in the middle of this hip street, both employees and customers were maskless.

VACCINATION

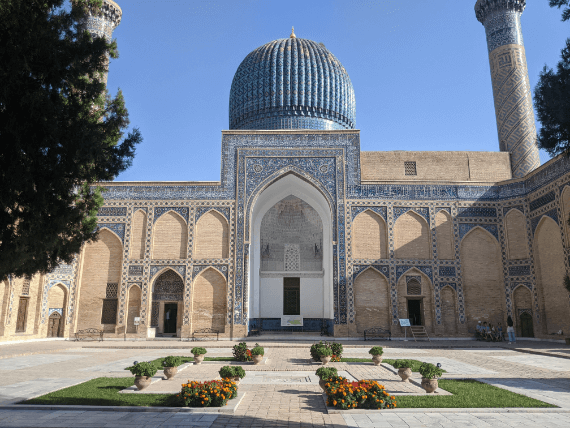

Uzbekistan was the first country where the topic of vaccination really came up in conversation. In Samarkand, as we were buying tickets to one of the major sites, one of the staff asked us about our experience with vaccination when she found out we were North American. Turns out she’d gotten a shot of Moderna (what was broadly referred to as "the American vaccine", with people often not knowing it was actually called and made by Moderna) the day before. Her arm hurt and she wanted reassurance that this was a normal symptom. Inside the site, the topic came up again. One of the souvenir vendors, unprompted, let us know that he was not getting vaccinated even if he had the possibility. "I am young so I won’t really get sick if I get COVID. I got COVID last year and I was fine, I just had fever for one day and then I was back at work." He added that his father was also against getting the vaccine even though he was in his fifties. In an interesting turn for foreign policy, there was particular skepticism about the efficacy of the Chinese vaccines. It is absolutely unquestionable that the vaccine effort is a boon for the technological reputation of the West. In Bukhara a few days later, we stopped in a little shop to get a drink. Upon finding out we were from America and Canada, the shop keeper also let us know that she’d gotten the “American vaccine” a couple of days before. We gathered that she’d been tired the next day and her arm hurt but she was very pleased to be vaccinated. Through a mix of sign language and Kevin’s pidgin Russian, we understood that once she got her second shot, she’d be able to put a sign in her shop window indicating that she was vaccinated. She was confident this was going to be good for business.

CROSSING BORDERS

When we arrived in the UAE, we needed to show a negative PCR test to get on the little train that takes you from the terminal to the main airport. After that, no one, including customs, asked any COVID related questions.In Kyrgyzstan, two flights landed at the same time and there was a mob of people trying to get past the two border agents checking proof of vaccination. By the time I got in front of the harried agent, he literally touched my piece of paper without looking at it before waving me through to the customs agents. No further questions.

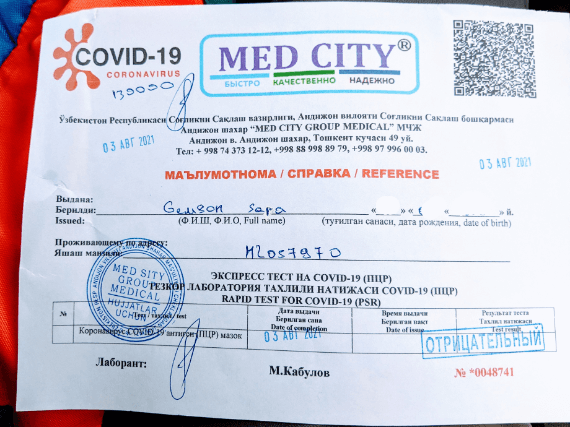

At the land border crossing from Kyrgyzstan to Uzbekistan, we had to do an antigen test. We paid the equivalent of $12 USD and a very friendly lady wearing a white lab coat and a hairnet, but no mask, tickled the inside of our noses with a swab. We didn’t have time to sit down before we were called back to receive our certificates declaring that we were negative. Unless Uzbekistan has invented the first instant antigen test, we’d just experienced a taste of COVID safety theater that parallels removing small bottles of liquids and shoes at airport security.

Our next obstacle came on our way to the US. Initially we thought there wouldn’t be a problem since Canadians are allowed to fly into the US with a negative antigen test as the only requirement. But after a few verifications on frequent flyer chat boards, we realized that we had a problem: our flight from Turkey was via Germany. This meant that the US ban on passengers flying from the EU applied to me. If we had flown directly from Turkey, no constraints. If we had flown from Georgia (which isn’t part of the EU, even though it really really wants to be), no constraints. But because we were stopping in Germany, in the airport, for 90 minutes, where we would just be going from one gate to the next, the flight ban applied to me. To marvel at the incoherence of this policy, here are the current COVID rates in these countries:

Germany: 11 cases per 100,000

Turkey: 22 cases per 100,000

Georgia: 70 cases per 100,000

USA: 46 cases per 100,000

(In the category of curious rules that don’t seemed to be based on science or logic, the Georgians, Uzbek and Kyrgyz all seem to believe COVID can be transmitted by your feet. They have added “disinfectant mats” at the entrance of official buildings, with signs that ask you to wipe your feet to keep COVID out.)

Fortunately, I am married to a wonderful man, who also happens to be an American citizen, which meant that an exception would be made for me as his wife. Except that we had to prove that we were married and we don’t make a habit of travelling with our marriage certificate. Additional hiccup: while it was safely tucked away in my parents’ basement, they happened to be in Quebec. Fortunately, my cousin came to the rescue, rooting around the basement on a Sunday morning, finding the certificate, scanning it, and sending it to us with time to spare before we left Turkey. It was definitely required as we had to show it in Istanbul when we checked in, in Frankfurt in a special clearance line for passengers to the US, and again in Houston, where I was put in a holding pen before being cleared by a second customs agent who reviewed it.

RECEPTION

While governments determine the rules that currently allow us to enter a country and under what conditions, ultimately for a trip to be pleasurable the people of the country must also want you there. So I was both pleased and relieved that people were nothing short of delighted to receive foreign tourists pretty much everywhere we went.The tourism sector has been decimated by the pandemic and it is only starting to reemerge very slowly. While we certainly weren’t the only foreign tourists, in countries like Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan there were only a handful of others, mostly from Western Europe. As we hiked through the Alay Mountains in Kyrgyzstan, I asked our guide if the families who were hosting us in their guest yurts had any concerns about us visiting during the pandemic. “Not at all! They know that the government has asked for proof of vaccination and would only let you in if it was safe.” Until May 2020, Kyrgyzstan had been entirely closed to tourism. In Uzbekistan, when we were asked where we were from, which was frequently, our response was always met with great enthusiasm. Or more accurately, Kevin’s answer of “America” was met with great enthusiasm, and my response, “Canada”, was often met with mild enthusiasm mixed with a dash of uncertainty. Something like “Canada….I’ve heard of that place…I think it’s pretty good…I believe it’s next to Narnia.”

In Georgia there were significantly more tourists than Central Asia, though we were told that tourism was still well-below pre-pandemic levels. Those we met were from both Eastern and Western Europe but none from North America. Again, particularly in the rural part of Georgia where we went hiking, people were incredibly happy to see us there, host us, and speak with us. It was clear that our presence was a sign of a slow return to normalcy.

The only place on the first leg of our trip that was buzzing with visitors was Istanbul. It is just such a big city in such a big country that it’s hard for it to look quiet. I can only imagine how crazy it must be during a normal tourism season. Needless to say, we went entirely unnoticed by the locals, who were very much getting on with life. The same has been true in Texas and the US Southwest, where visitors from Canada are essentially seen as identical to any other domestic tourist, of which there are many.

WHERE WE GO NOW

Particularly with Delta, it seems that Covid is not a malady that will simply disappear from the planet. As vaccines spread to the remaining unvaccinated corners of the planet - largely in Africa - over the next few months, decisions need to be made. On the side of government, what can be done to smooth international travel, for tourism, family reunions, and business? And on the side of individuals, how comfortable will it feel to travel?The first question should be easy. Governments need to have a common and simple standard. Vaccine records should be stored in a uniform format, with countries respecting effective vaccines even if they were not used domestically - Canadians and Germans who got one shot of AZ and one shot of Pfizer would not find their vaccine counted in many places right now, to say nothing of the billions who have a Chinese, Indian or Russian vaccine. Second, PCR test requirements are incredibly expensive and no better than rapid tests at finding travelers who are currently infectious. It is not reasonable to ask all visitors to take a $200 test that is often hard to acquire in developing countries and letting that test be three to five days old on arrival anyway. Solely because of path dependence, many countries officially require "RT-PCR" tests, even though equally sensitive and far cheaper technologies like NAAT and Abbott ID NOW have come on the market.

On an individual level, though, the news is much better. We have been able to do literally everything we wanted to do as a tourist everywhere we have visited this far, and we have not had a single instance of a local person objecting to our visit; indeed, quite the opposite is true, as locals seem anxious for tourism to return! With vaccination rates only increasing, 5.7 billion doses have now been given worldwide, I very much look forward to most of the world benefiting from the protection vaccination offers so that we can all return to normalcy. Even if that means a return to crowded tourist sites.

Text by SC

Chinle, Arizona

Sept 9 2021

Tweet